Women in The Flat Knitting Industry

Is Technology the Great Equalizer?

We sit in 2018 and we’re hearing about gender gaps being significant in many industries; women falling out of STEM jobs at 45% higher rate than men; reports of bad behavior and discrimination by men being ignored by HR at major companies; women still being under paid as compared to men doing the same jobs, especially in technology, start-ups, and sports equipment companies.

Silicon Valley Underpays Women

Why Women Leave The Tech Industry

And it got me thinking – has anything changed since 1983?

Above: Nina

My name is Connie Huffa, and I’ve been a knitting engineer for over 30 years. By far, my favorite part of building textiles is getting up to my elbows in yarn and punch tape on a knitting machine. In 1983 when I started out, I was the odd female with a tool belt and a handful of floppy disks; a teenager working in a factory to pay for college.

Over the past 40 years the textile industry, its machinery, its people, its markets have changed considerably. The flat knitting industry is no different. Machines have grown quicker, smaller, and more precise, driving up product innovations, and the cost to make those products down. The variety of things we can make on them has gone way beyond apparel. How people use machines and who is now using them also has changed over the years. What no one really talks about is the ‘Third Industrial Revolution’, and how the shift from mechanical to electronic selection changed the demographics of technicians, designers, and knitters.

But even if technology has changed, and the skill sets required to work hands-on machinery have changed, has the landscape of the industry changed enough to include more women?

To answer that question, perhaps 2018, the year of the woman, is high-time to hear from the women in our industry.

In part one of our series, I’d like to introduce you to Monica, Nina, Nastia, and Florina. These knitting professionals take you to Italy, Germany, USSR, Romania, The UK, and the USA. Experience in this group spans 1983 when I started to the present-day entrants into our industry, like Florina. My colleagues were gracious enough to share of their joys, challenges, and opportunities for women, working on machines in our industry, answering 15 questions from how they got started, and where they see the role of women in knitting the future.

Above: Nastia

A little bit of background on our flat knitting industry:

The Third Industrial Revolution started to materialize in 1969, and is best evidenced as the integration of computers and electronics into machinery: transistors, microprocessors, telecommunications, space research, biotechnology, automation, programmable controllers, and robotics. This progress in technology changed all industries. For knitting it amounted to a revolution, triggering an explosion in fashion and production efficiencies, where no longer did factories need to stick with small jacquards limited by mechanical machines.

The Challenges:

Making samples back then took significant resources of the production team in time, know-how, and sometimes brute force. Designers would draw, select yarns, and technicians would translate into what worked on the machines. Anyone who has ever punched steels or pushed in pegs can tell you how challenging it was to work on mechanical machinery, and be creative within the limitations of twelve to twenty-four needle repeats; punching paste boards and knowing by heart the movement charts that ruled the capabilities of the machines, as well as the factories. It took ages to go from concept to finished product.

Working on those earlier generation of 1960’s and 70’s machines is challenging for anyone, but more so for women. Why? Mechanical machines are heavy, temperamental, and require the right touch – sometimes with a hammer, like the autos of those days. And just like cars, machines require oil, grease and at times, a good shove to set up, run, and repair. They break down frequently and are cumbersome to configure I once worked in a factory in Uruguay, where a complex design was set up by a tech for an intarsia on an Ajum in steels. When the first fabric came down, the words were backwards. In mechanicals mistakes aren’t necessarily obvious until the machine is running, or fabric is knitted. Many of these machines have found homes, working in emerging markets.

The words knitting technician conjure a specific profile of that role in the textile industry – even today. In previous generations the title of machine mechanic or technician was held by men with few exceptions. Women were design majors, merchandisers; created croquis, pattern graphs, line sheets, and no one really had any hands-on machinery. There were few women that wanted to work on machines in the 70’s, 80’s, and 90’s. However, it’s also no secret that for the role of working on machinery, women were not encouraged.

The Opportunities:

Today, people who work on newer electronic machines don’t really understand what it was like to not have a comb, clamping, electronic stitch cams, memory on the machines, and CAD systems. Take down systems were literally swinging weights that could smash your knee cap if you weren’t careful. Stitch cams were adjusted with a screw driver, and for heaven sakes, don’t let go until you tightened the screw or it was a half hour to get the stitch cam calibrated again. Working on machines cuts fingers, breaks nails, grabs your hair (my ponytail), and leaves many with perpetual oil-blackened fingers and arms.

Stoll Ajum knitting machine

In the early 80’s when I was in college at Philadelphia College of Textiles and Science, working for PVH Somerset, and this Third Industrial Revolution was in full swing in our industry, I didn’t realize that working on knitting machines was a man’s world. In between spools of punch tape and fixing broken needles, I looked around and realized that even at my college all the weaving looms and knitting machines were taken care of by men. Yet at the factory, I was designing for all types of machines Shima, Bentley, Jumberca, Universal, Steiger, Wildman Jacquard, and others. Why? Computers were just getting into our industry and most all of the mechanical technicians thought they were a fad; they didn’t want to learn CAD, and quite frankly didn’t have the time, since they were constantly fixing and punching cards. In some cases, they didn’t have the creative capacity to work with a screen, rather than tangible cams, paste cards, and movement charts. That was the first time I heard, ‘give it to the girl.’

So, Dave Ferret, the Chief Production Engineer did just that, and thanks to his confidence in my abilities, (and the fact that none of the guys wanted to do it), I fell in love with Shima flat machines, learned how to program, punch tapes, tie up yarn, and ran the machines. Running the machines, using the programs I’d created, was a big deal because I had to fix the mistakes I made; no pointing fingers. That’s the best way to learn, even if it didn’t feel like it back then.

Of all the hundreds of male technicians and mechanics in the 80’s, I knew of only three women who worked on machines: Nancy Burton also at PVH Somerset, Pat Sheu at Stoll, and me. Women in our industry, at that time, were designers, created croquis, pattern graphs, mood boards, illustrations and didn’t work hands on machinery. Few knew the capabilities of machines, beyond twelve needle repeat fair isles and Vogue knitting textures.

The day I did my first program from start to finish, I realized that electronics were the great equalizer in our industry. I could design jacquards, write programs, punch tapes, and in a matter of a couple hours the machine was up and running samples or production. This would take days or a week on the old mechanicals. At the time, it was exciting to see first-hand how electronic controls quickly made fashion trends happen. The leading edge of the industry has always been creativity. Changing styles quickly, and breaking the restrictive mechanical chains that limited creativity created an explosion and ignited passions for knitting from the technicians to designers and end consumers. Our industry doubled its creativity and imagination because electronics made what was once cumbersome and time consuming, light, precise, and fast.

Even with all the advancements in technology, it wasn’t easy working on the new electronic machines either. Why?

1) Taking off the cam box to find a broken butt was impossible for me to do alone: It was darned heavy;

2) Machines were built taller then and I was only 5’5’’, I couldn’t pull it straight up without damaging parts even with a stool; (Machines today are set lower.)

3) Pulling the cam box off, you then need to flip it upside down onto another surface to get to the cams, to inspect for broken buts or damaged cams. I didn’t and still don’t have the upper body strength; (Today's cam boxes are small, compact - Easy yo pull on and off.)

4) Not many (men) would trust a woman to fix the machine and get it running again, which I and others were totally capable of doing.

Florina

The opinion of women working on machines: has it changed?

The mindset of men not really trusting a woman’s work to be as good as another man’s has followed me most of my career in flat knitting, even when I worked for a major machine builder. This is in stark contrast to how I’ve been treated as an exec in other industries, including many times, when I’ve been the only woman in the boardroom.

I remember being on a training course at a machine builder in 1989 and asking a technical question about how to build intarsia all the way into the rib on the new belt drive machines. The instructor told me flat out that if my husband, Bruce, wanted to ask a question, he should call him directly. I told him it was my question. To this day he's never answered me. But, here's the thing with most women: we don’t give up and we’ll figure it out.

Another time in the 90’s, when I was freelance tech in Los Angeles, I remember a male technician, who I knew well, being concerned that I was paid the same as him at a factory. The owner told him that I did the same work as he did, if not more. I was seven months pregnant before I ever told the same factory, for the same reason.

Many times, including recently, I’ve been with my husband at a machine builder or trade booth and I’ve asked technical questions, and the male technician turns to my husband and answers him. My husband didn’t believe it when I told him the first time, but later saw it for himself and now tells these people to answer me directly. Why does this even happen in the first place? It’s not even decent manners. I can’t even imagine how other professional women get answers. I’ve been to several trade shows (ITMA, TechTextile, IFAI), visiting flat knitting machinery. A few times, when a women came to the booth, asking questions about the machines, the men on the booth did not even get up. I’ve walked over to them, stated I wasn’t associated with the company, but I answered questions. Why is treating women as machinery customers still such a problem in 2018?

Actions and company culture speak volumes. Women are not traditionally in the flat knitting machine builder culture, no matter the brand. Up until the last two years, there have been no women executives, and not even a women’s bathroom in the advanced machine area of a particular machine builder. I need to travel two floors before I find a women’s restroom. I don’t drink when I visit for that reason. Today, as far as I know, there is only a lone woman VP at all machine builders combined, and that is pretty sad for an industry that has been around since 1883.

What are other women’s experiences around the world? And how do women just entering the industry view our industry and their opportunities? 2018 seems time to look around to see how our industry has changed for the better or worse for women in knitting. What are the challenges and opportunities in working on machines today versus yesterday? Our goal is to discover why we have such a passion about knitting, where our inspiration comes from, and what we see for the future of our knitting industry regardless of gender. In this edition we visit with:

Nina C. Dorfer is originally from Austria and is working in Germany and the UK. She’s a Senior Technical Textiles Developer. www.ncdor.co.uk

Monica Lasagni is from Italy. She’s a technical 3D knit specialist from Stoll Italy in Carpi, has studied languages and worked at Miss Deanna for 5 years programming machinery

Nastia O, is a knit engineer and developer of 3D seamless textile parts and components for industrial and soft goods applications.

Constantina Florina Natea (Florina) works in the UK, but is originally from Romania.

1. How long you’ve been working on knitting machines?

Nina: Since 2012, I started out programming at university where we had 4 semi-old Stoll machines

Nastia: For the last 19 years

Monica: Since 1986

Florina: I started working on knitting machines in 2012 – present

2. On what types of knitting machines do you work? What’s your favorite?

Nina: At the moment on CMS 530 14gg and ADF 14gg, really enjoyed the K&W 5,2gg as well when I was working in the UK

Monica: I programmed Jumberca (circular machines) first and then Stoll, Zamark, Rimach, EMM flat Knitting machines. ]What’s your favorite?] Of course, STOLL!!!

Nastia: I started out with hand driven knitting machines back then, got through a V-bed period and now work on Stoll machines. From their lineup, I love newer ADF generation, but I also enjoy working with older workhorses like 330s and 530s.

Florina: In our showroom we have only Stoll machines in different gauges : CMS 530 HP (E:7.2 ; 3,5.2: 2,5.2; ) ADF (E:16 : 7.2) CMS 520 C+ (E: 1,5.2) CMS 822 (e:7.2)

3. What event motivated you to become a knitting professional?

Nina: My knitwear teacher at university – he always responded to ideas with: ‘that’s not possible’. At one point I didn’t believe him anymore and decided that I would never want to depend on a knitting technician.

Monica: I think I started to be involved in knitting thanks to a “DNA heritage”. When I was a child, my mum used to work at home, using flat knit hand machines, and I spent with this “sound” the first 6 years of my life. When I finished my studies, I started to work at my uncle company…. A knitting company!!!! And I was so much ignorant about knitting that I started to attend evening courses and new job opportunities came very quickly. I spent the rest of my days in this field that I still love it so much.

Nastia: I always knew it was my field since I was a kid. I self-taught myself how to knit when I was 8 after watching a TV show. Because it was in the USSR, there was no way to record the show, but I remembered the idea and started to save money to get knitting needles. By the time I got them, however, the technical details had long vanished from my memory, so I invented my own way to cast-on, to hold the yarns, etc. It was my little lesson in looking for new solutions to an existing problem!

Florina: After I graduated an economics university in Romania, I couldn’t find a job that matches my degree so after one year I took whatever job I could find and it was in a knitting company.

4. Who or what inspires you now and why?

Nina: Old-school knit pros who teach me tips and tricks, newbies and students who love to just make stuff and all sorts of new material innovations to play around with and explore properties through structure.

Monica: Anything is inspiring me. I can look at a painting and think about making something similar with knitting. Unfortunately, I don’t have enough time to develop all what is coming to my ideas.

Nastia: I follow very closely academic research in knitted structures, the innovation in fiber development and machine builds to which I contribute myself. I admire people who are trying to move the industry forward. On the clients’ side, any manufacturing company that takes a risk to adopt the knitting technology to improve their process is in inspiration. So many things are completely new in technical textiles, and each one is exciting!

Florina: One day I hope I`ll be like one of our senior technicians, so knowledgeable in programming and in fixing the machines.

5. What makes you smile the most about what you do?

Nina: That it is hell and heaven at the same time.

Monica: Any time a swatch comes out the machine, is a new surprise!! And sometimes it happens that what is coming out is not wat I expect. Every little change gives different results, sometimes very different results!!!

Nastia: When I make work a technically insane thing that no one thought could work. Another smile when I make it ready for production.

Florina: I love to meet new people every day. I enjoy working with designers and finding out about their career.

6. What makes you most proud of yourself as a professional?

Nina: Being able to create anything with a single thread of yarn through programming and independently handling/repairing/maintaining a big piece of machinery.

Monica: The love I feel, and I put on knitting. Creativity is a part of myself that makes me feel alive.

Nastia: A long list of challenging problems that I solved for people that I know would benefit the whole industries.

Florina: It feels good when I have a challenge. Something I would never think about and our designers would ask for it ( a complex combination of structures or 3d knitting ) and by the end of the day I would find a way to do it. That makes me proud, to see that I can do things I would never consider.

7. What has been the most significant barrier in your career?

Nina: The hardest part was entering the industry and actually gaining experience, men were being ageist and sexist towards me, even though I saw a lot of men my age and with less know-how being hired and some companies took advantage and didn’t want to pay at all. You basically just have to figure it out on your own, jobs are rare and remote, and it takes a lot of compromise in other areas of life.

Monica: Sometimes it is necessary to be a “realizer” instead of being a “creative”. When I was a knitting programmer I have been involved in companies that did not realized how important is this role/position for the best result of the sampling. I also don’t like when the sample is not working well, and I have to modify it many times since it is OK.

Nastia: Surprisingly, lack of open communication with other knitting engineers and lack of industry standards. We don’t have a GitHub for our programming, there is no certification, we don’t even often get an advantage of being able to say whom we developed for. So other than the word of mouth, how do companies who seek knitting engineers differentiate between a person who’s top skill is producing nice flat samples from a person who makes multi-layer 3D?

Florina: I don`t feel like I had a significant barrier in my career, but one of the obstacles I often come across is when I`m being sent to a knitting factory. When they see me, the first thing they tend to do is to underestimate me.

8. When you began your career years ago, did you ever imagine that you’d be a key knit professional in a male-dominated profession?

Nina: I never doubted that I would get to where I wanted to get, but I never imagined the journey to be that hard and with that many obstacles.

Monica: I was conscious that it was a job more for males than for female. But only because males have more mechanical capabilities. I have seen machines modified to achieve better techniques. I am pretty good with practical activities and I used to operate on machines even for changing broken parts or cleaning, or other simple mechanical activities. Of course, for difficult situation I used to call an expert technician. But I have seen many times that most of the males used to “realize”. What I noticed I had in addition, as a woman, was the creativity, the ability to interpret even a little picture or a sketch, the good taste with colors and fibers.

Nastia: I had no idea. Back then, an image from the textile industry was rows of women at a factory floor.

Florina: To be honest I didn’t think “I`ll survive”, only because I was surrounded by men. But when I started working at STOLL GB and I saw I`m not the only female it felt so good!

9. What was the organizational culture like then for you and women working hands-on in the industry? How is different today?

Monica: I think that males can decide to invest all their time at work. Women usually also takes care of the house and the family.

Nastia: It was such a low-prestige, dead-end occupation for women who could not go higher than an assembly/finishing line worker then. Now I do not see such a ceiling, but I often see a surprise in the eyes of a person when I tell them what I do. Once, on my first visit to a client’s site as a lead textile engineer, a male employee noticed me, said hi, and asked if I was their new secretary. It sounded like it never occurred to him that I could be anything else than a secretary. Later, I found out that all the employees there were male.

10. Did women knit technicians have a hard time getting promoted then? Do you know if you/they were paid the same?

Nina: I don’t know about back then but today I often wonder if my salary is equal to my male colleagues, it’s not very transparent.

Monica: I cannot say if I am or I was paid the same as my male colleagues, but I have the feeling of having less opportunities. Women also have family duties that male generally don’t have, and it is like to have 2 jobs instead of one. Energies must be split, of course.

Nastia: Where I grew up, it was the lowest wage occupation so what I heard being said was that no man would ever take such a job. It was considered below men’s threshold, you see.

Florina: Taking in consideration that my other male co-workers are senior technicians, and their experience is huge in this field, I believe that they are being paid more than me.

11. Have you ever experienced resistance on the job or not been taken seriously in presenting to male technicians or male managers?

Nina: Yes, some of the managers who are 50 and older haven’t taken me seriously, excluded me from meetings because of my age and gender, put me down in front of my colleagues and made me responsible for anything while acting like ‘buddies’ with male colleagues.

Monica: Yes, I had this experience and I think it is time to step forward.

Nastia: I saw male co-workers pretending I was “some sort of a designer” and not treating textile engineering seriously. I think a big part of that comes from the field of 3D knitted technical textiles being relatively new. It is still being confused with a low-tech surface design or “traditional” fully fashioned apparel development.

12. Is there any event that stands out in your mind that defines that resistance?

Nina: I got excluded from a meeting in a company in Germany once about production efficiency and organising the machine operators – even though I was programming and handling production issues. When I addressed that matter to my boss he said I’m not 50 years old, so I don’t qualify to be in the meeting. That is just one of the things that boss said to me during my time there.

Nina: Another time I got offered to work at a small agency in the UK to do fashion prototypes, it was a trial-week for possible employment and I was told to be paid. When I sent over my invoice for travel costs and work-time they stated to be surprised to receive an invoice and claimed to never have offered pay.

Nastia: I think that “Oh, you must be our new secretary” thing tops it all.

13. Do you feel the industry today makes efforts towards improving the culture for inviting more women to enter technical knitting jobs?

Nina: So-so, I see a lot of women being interested in taking on knit development and getting their hands dirty on machines, but company owners not taking that interest seriously and promoting or supporting that and instead only hire them for traditional roles.

On the other hand, when working with experienced technicians or Stoll employees they definitely treat women on eye-level. I think Stoll is a very good example and acts progressive in that realm.

Monica: Some companies have kindergarten and restaurants at their inside. Some companies allow flexible time (the possibility to organize the daily schedule) or even a part time. Some companies allow to bring dogs at work.

Nastia: I see people with backgrounds other than textiles entering the industry, and most of them are male – and very talented and bright male. That’s the fresh brains that we so much need. At the same time, female knitters who are the majority at any given college program dissolve between the designer jobs after graduation. At industrial level, there is more science to knitting than art, and probably it is not communicated enough in an inviting manner to the students, and they shy away.

Florina: Yes, I honestly feel like the industrial knitting machines we have on the market at the minute are more user friendly, and replacing parts is so straight forward.

14. Do you feel that the machine builders respect you as a knitting professional in the same way as your male counterparts in the industry? If no, how can they improve their efforts?

Nastia: I do feel very respected but it’s not that clear among whom. I can come up with maybe ten names of knitting engineers in the U.S., but ask me to name twenty, and I’ll balk.

15. What advice would you give to the next generation of female leaders in the knitting industry?

Nastia: You are needed. You won’t have much company, but the one you will have will treasure you.

Monica: Cooperate more and be respectful, create new ways of working instead of playing “power” as males often do.

16. Is there anything else you’d like to add?

Nina: Yes, the industry should definitely make a hell of a lot more (financial) effort to bridge education and industrial landscape to build a new generation of hybrids.

Monica: Knitting is so magic!!! Nowadays knitting is expanding in new areas, different from the “simple” apparel. The way you do what you do, can make the difference. I hope people can see this difference. Thank you for giving me the opportunity to be part of your survey.

Nastia: My dream is to make 3D knitted rockets – which is, to replace hard rocket components with reusable knitted composites which will enable missiles to carry bigger loads faster and more economically. And I am deadly serious about this. PS – I also hope to live to a day when I’ll have a 96” wide 3.5.2 ADF in a T-bed form!

Monica

The Future:

Technology can be the great equalizer in creating opportunities to innovate. Utilizing half our industry is hamstringing it. Machines, yarns, and stitches inspire everyone – no matter where they are in the world. As a woman who’s been in this industry a long time, in spite of the gender challenges along the way, this feedback from women in our industry is encouraging in some areas, and in others it shows our industry still has a long way to go in respecting women as contributors and professionals in our industry. We as professionals hope that the machine builders, factories, and manufacturers will welcome, encourage, nurture, and appreciate that women and all people have the same desire to create, and a driving curiosity to learn on the machinery, beyond WYSIWYG cut and paste. We all should feel welcome to dig in and do whatever inspires us on a machine, and be respected on a deeper level than “Oh, you must be our new secretary”. Certainly it’s going to be up to us ladies to change the stereotypes of what a technician looks like in people’s minds.

Connie Huffa – Fabdesigns, Inc.

Copyright © 2018 Fabdesigns, Inc., All rights reserved.

Note: The above excerpt on Industry 3.0 in the knitting industry is a portion of the seminar presented by Connie Huffa of Fabdesigns, Inc. at IFAI advanced Textiles Expo October 15, 2018 as part of Digitalized Manufacturing: Will the Fourth Industrial Revolution Transform Flat Knitting?”

Fabdesigns, Inc. address: 327 Latigo Canyon Road, Malibu, California 90265

Website: www.fabdesigns.com

Email questions of comments: info@fabdesigns.com

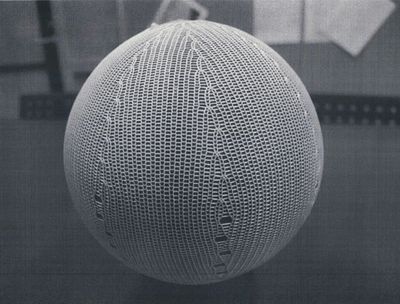

Fabdesigns 3D knit sphere 2006 by Bruce Huffa

Cookie Policy

This website uses cookies. By continuing to use this site, you accept our use of cookies.